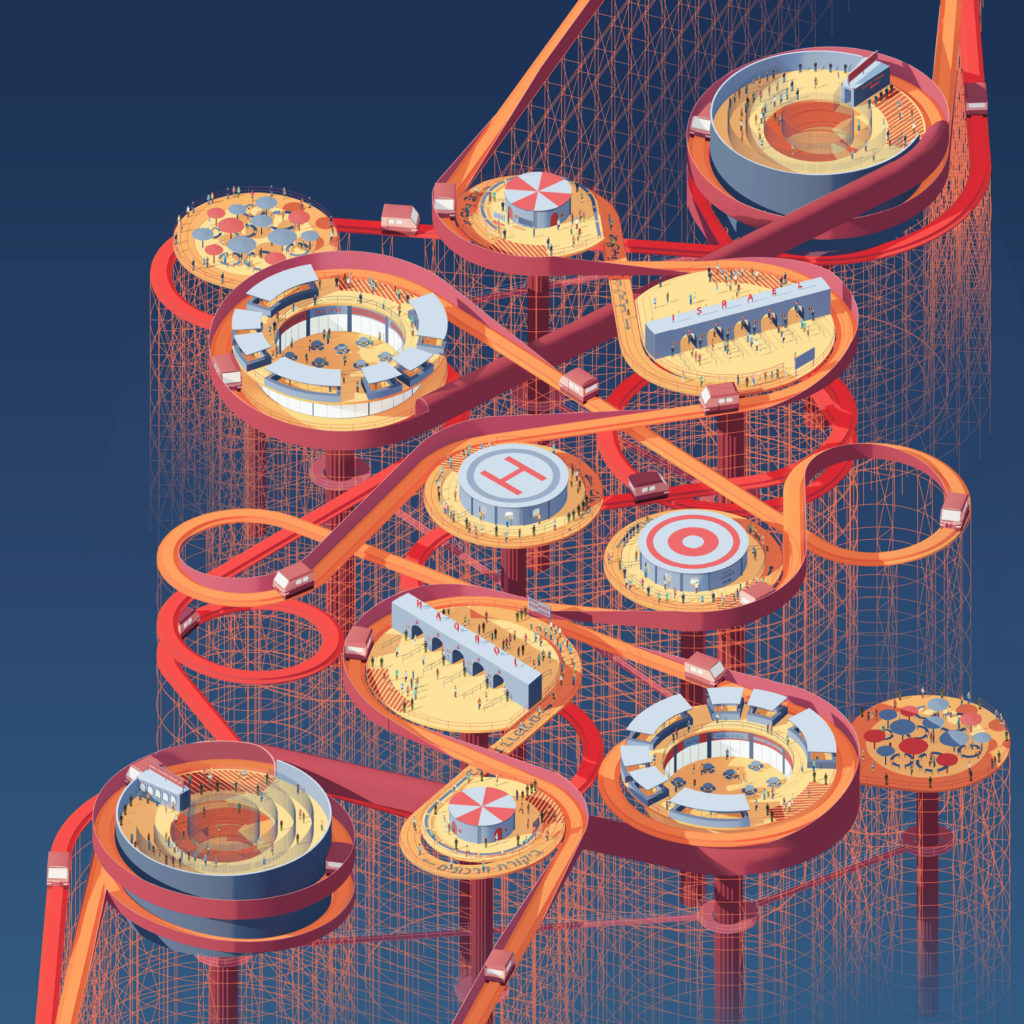

All at Sea, a winner of Architizer’s One Drawing competition, by McGill University students Amélie Savoie-Saumure, Pascale Julien and Matt Breton-Honeyman.

With computers able to imagine and grow architectural structures of unbelievable complexity, and in record time, is there still a place for drawing by hand?

The Secret Life of the Pencil, published in 2019, is a wonderful book. It features close-up images of the pencils used by some of the world’s most creative thinkers — Thomas Heatherwick, Philippe Starck and James Dyson among them. We tend to think that computers have dominated every facet of our working lives, but this small book is a poetic reminder that assumption may not necessarily be true. Flipping through its pages of such well-used leads, one wonders if computers will ever be able to replace one skill only humans know how to do, which is to draw.

Pencils owned by Thomas Heatherwick and Sir David Adjaye, from The Secret Life of the Pencil (Laurence King)

In another era, sketching was a daily routine for architects. It was a way to work through problems, or to imagine what a building might look like in its completed form. Today, fingers have mastered the keyboard and architectural visualization can imagine structures of unbelievable complexity. Just looking at the sinuous buildings of Zaha Hadid and it is easy to see the impact of computational technology has had on the built environment.

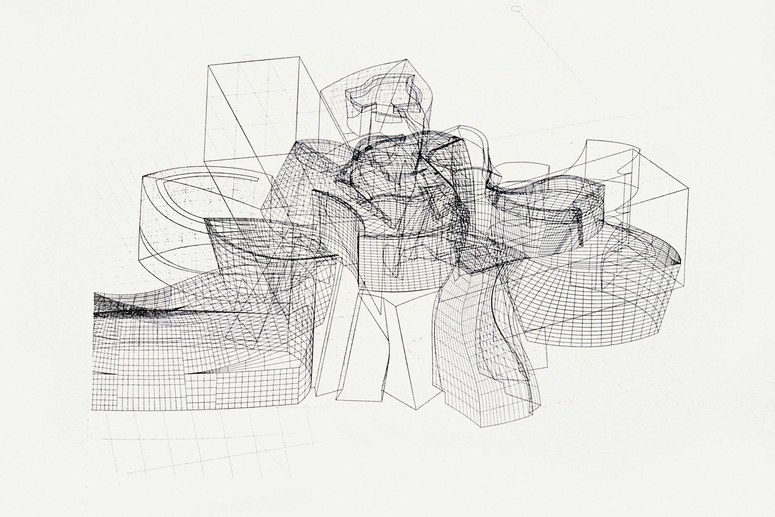

Frank Gehry used CAD programs in 1992 when he designed Guggenheim Museum Bilbao © Photo: Gehry Partners, LLP

Every architecture student is now expected to excel at CAD. Does that mean the characteristic signature of the author is lost? That question is now circulating within the professional rendering world. Chaos Group, a 3D computer graphics company based in the U.S., recently hosted a podcast series and invited Matthew Bannister, founder of DBOX, to provide a brief history of how hand rendering shifted to the kind of immersive experiences his company now produces for such global firms as SOM and Herzog & de Meuron. The V-Ray technology DBOX employs rivals that of cinematic Hollywood movies. Bannister founded his “arch-viz” agency in the early 1990s, when watercolour proposals were still the norm. “There was an ‘avatar moment’,” he says, when clients wanted to see their ideas presented as 3D renderings. “It was a slow and incremental change, not sudden. Today, they understand there is value in telling real stories and that it requires a substantial front-end investment.”

DBOX’s visualization of a 35-storey tower overlooking Central Park won a Golden Medal of Montreaux in 2018 for its corporate imagery.

Bannister also wonders about the loss of authorship. After all, renderings, whether hand-drawn or computer generated, are what sell an imagined project to initial investors, and yet there is rarely credit given. Renderings also advance innovation. They are the only way of presenting over-the-top ideas that aren’t yet constrained by structural logic. In other words, it must be drawn before it can get built.

Shouldn’t renderers, then, be acknowledged for the vital role they play in propelling projects —especially wildly ambitious ones — into reality? Bannister was bothered enough by the lack of authorship that he launched an Instagram handle called The Credit Revolution, to encourage architectural visualizers to champion their artistry in the same why firms credit photographers who document completed work. His efforts have yet to start a revolution, but the tide seems ripe for change.

Thecreditrevolution’s aim is to ensure renderers are valued fairly by architecture firms and the media.

Interestingly, even hyper-technology hasn’t erased the art of drawing. As the Secret Life of The Pencil reveals, many of the most creative thinkers of the 21st century still rely on pencils and sketchbooks. Drawing still scores high for qualities computers simply can’t simulate. For instance, it easily crosses boundaries between the technical and art. Sketches can also hint at volumes or merely evoke an atmospheric mood. Frank Gehry’s sketches are famous for illustrating a building’s shape, form and poetry within just a few dozen squiggly lines. While computers solve problems in a blink of an eye, pencils force creative minds to consider scenarios and work through them. Unlike keyboards, the act of drawing bypasses mundane consciousness and reaches straight to the brain.

After Work, a finalist of Architizer’s One Drawing competition, drawn by Yoonsoo Kim and Christoph Schmollinger.

Each drawing type has its advantages, of course, and the architecture industry would be unthinkable without both. That may be why Architizer has honoured each art form’s uniqueness with the launch of its annual One Drawing Competition and One Rendering Competition. The submissions sent in for each are breathtaking. The real focus is not method; it is about beauty and the aesthetics that can inspire us to think in new ways.

Based on an article by Barbara-Jahn Rösel originally published for the German ARCHITECT@WORK newsletter.